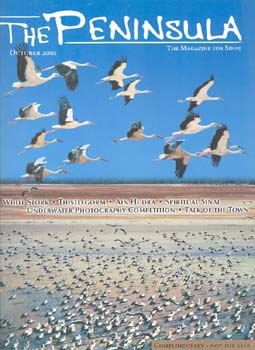

Stork soaring mad

© Chad Clark 11-9-01 As regular readers of the Peninsula may remember, I was

visited by the stork last November 5th when she delivered to me my first-born

son, Sebastian. In fact it’s not uncommon for the storks to visit Sharm el Sheikh,

albeit usually a little earlier in the year. Apart from the recent increase in a new

generation of Sharmers, the White Stork visits our outcropping of fossilised coral on an

annual basis every summer.

As regular readers of the Peninsula may remember, I was

visited by the stork last November 5th when she delivered to me my first-born

son, Sebastian. In fact it’s not uncommon for the storks to visit Sharm el Sheikh,

albeit usually a little earlier in the year. Apart from the recent increase in a new

generation of Sharmers, the White Stork visits our outcropping of fossilised coral on an

annual basis every summer.

Whilst winging their weary way on a ‘winter sun’ holiday, away from the cold daunting winters of north eastern Europe to an altogether more enticing sun stricken South Africa, Ciconia ciconia stop off here on their southbound journey for a well deserved break. They are a soaring bird, relying on thermal air currents to keep them aloft on their long journey, and they try to avoid flying over the sea which lacks this aerodynamic assistance. Originally, they would have landed in the shallow areas of water around our coastline and waded around in a few inches of water looking for food, well away from the deeper sea in which they would drown. Nowadays, they see and smell the appetising stagnant waters and abundant food supply of our sewage works and refuse dumps. Living on a diet of anything from insects to small rodents, the stork is an opportunistic feeder and will forage for all kinds of nutrition, stalking about and jabbing at almost anything with their beaks.

With a regal

wingspan of 2 metres, standing tall and proud on their metre long legs, with their black

and white plumage subtly offset by their red beaks, they are regarded as good luck symbols

of fertility for reasons lost in the mists of time, bearing babies across the skies to

happy couples. Weighing anywhere between 2 and 4 kilos apiece, their nests are normally

quite huge affairs, 2 metres across and 3 metres deep, made up of twigs and branches,

lined with softer grass, rags, paper or whatever is to hand. Passed on like the family

home from generation to generation, these nests are ringed each year with a new leafy top.

The mating pair return home to the same nest year after year, even though they holiday

apart, and go through the same old ritual involving a lot of wing flapping, neck thrusting

and machine-gun like bill rattling, finally settling down to produce a few eggs around

April time which hatch a month later. Both male and female parents take care of their

young for the next couple of months. Shortly after the fledgling young are able to sustain

flight, around July / August time, they migrate to the warmer climes of South Africa,

stopping off for a couple of days rest en-route at the South Sinai Service Station. The

first to arrive here are the mature, healthy adults, followed by the young, the old and

the weak. Surprisingly, most of the birds cared for by our Wildlife Centre in Coral Bay

are

With a regal

wingspan of 2 metres, standing tall and proud on their metre long legs, with their black

and white plumage subtly offset by their red beaks, they are regarded as good luck symbols

of fertility for reasons lost in the mists of time, bearing babies across the skies to

happy couples. Weighing anywhere between 2 and 4 kilos apiece, their nests are normally

quite huge affairs, 2 metres across and 3 metres deep, made up of twigs and branches,

lined with softer grass, rags, paper or whatever is to hand. Passed on like the family

home from generation to generation, these nests are ringed each year with a new leafy top.

The mating pair return home to the same nest year after year, even though they holiday

apart, and go through the same old ritual involving a lot of wing flapping, neck thrusting

and machine-gun like bill rattling, finally settling down to produce a few eggs around

April time which hatch a month later. Both male and female parents take care of their

young for the next couple of months. Shortly after the fledgling young are able to sustain

flight, around July / August time, they migrate to the warmer climes of South Africa,

stopping off for a couple of days rest en-route at the South Sinai Service Station. The

first to arrive here are the mature, healthy adults, followed by the young, the old and

the weak. Surprisingly, most of the birds cared for by our Wildlife Centre in Coral Bay

are  suffering from dehydration and various

ectoparasites rather than from any human impact. Very conscientiously, the local dive

operations and boats report any sick birds they come across, which are then picked up,

treated and released to continue their journeys. This August, for example, a flock of

17,000 birds were counted by National Park staff in one area alone. Each year, around 400

birds are treated during the migratory season of which, incidentally, an average number of

2 are surprisingly but completely black!

Like so many species of wild animal,

the White Storks existence is under threat, both in its native habitat and in its winter

refuge. Those that stop off in Sharm are originally from Eastern Germany, Poland and

Hungary, where their grassy plains and marshlands are fast disappearing. Those from the

West suffer a slightly different threat. Since they

suffering from dehydration and various

ectoparasites rather than from any human impact. Very conscientiously, the local dive

operations and boats report any sick birds they come across, which are then picked up,

treated and released to continue their journeys. This August, for example, a flock of

17,000 birds were counted by National Park staff in one area alone. Each year, around 400

birds are treated during the migratory season of which, incidentally, an average number of

2 are surprisingly but completely black!

Like so many species of wild animal,

the White Storks existence is under threat, both in its native habitat and in its winter

refuge. Those that stop off in Sharm are originally from Eastern Germany, Poland and

Hungary, where their grassy plains and marshlands are fast disappearing. Those from the

West suffer a slightly different threat. Since they migrate via Gibraltar, large flocks circle

the Western end of the Mediterranean and become easy prey for hunters. Even upon arriving

in their ‘holiday resort’ they now find that drought, overgrazing and the

indiscriminate use of pesticides has depleted their food source further. Those that

survive the arduous journey back home may well arrive in a worse state than when they

left, which does not bode well considering it’s only just at the beginning of the

mating season. Sounds like most of my holidays actually, apart from the mating

bit……

migrate via Gibraltar, large flocks circle

the Western end of the Mediterranean and become easy prey for hunters. Even upon arriving

in their ‘holiday resort’ they now find that drought, overgrazing and the

indiscriminate use of pesticides has depleted their food source further. Those that

survive the arduous journey back home may well arrive in a worse state than when they

left, which does not bode well considering it’s only just at the beginning of the

mating season. Sounds like most of my holidays actually, apart from the mating

bit……

back